By Sophie Lanoix

Neuroscience is booming and the amount of brain research has exploded in recent years. There is a growing understanding of how the brain works and, more importantly for us, how humans learn. However, we are realizing that some widely held beliefs are wrong and that many myths persist about how the brain works and its impact on learning.

A Quebec study (Blanchette Sarrasin et al., [accepted]) identified the five most popular neuromyths among Quebec teachers:

- Students learn best when they receive information according to their preferred learning style.

- Students have a predominant intelligence profile, e.g., logicomathematical, musical, interpersonal, which must be taken into account in teaching.

- Differences between students with dominant left and dominant right brains may help to explain differences in learning observed in students.

- Short coordination exercises, such as touching your left ankle with your right hand and vice versa, can improve communication between the two hemispheres of the brain.

- We use about 10% of our brain.

I have not found a similar study for myths about workplace training, but I often hear training professionals dispelling these same myths. It’s high time to put an end to them! In this article, let’s start by addressing learning styles and the learning pyramid.

Myth #1

Training needs to be tailored to the learner’s learning style

The myth

You’ve heard it before, that’s for sure. Regularly, someone will proclaim that we have to adapt our training to the learning styles of the participants because we learn better if we receive the information in our learning style.

What is true in this myth

There are studies that show that a person may have a preference for receiving information. As a result, several studies have tried to prove that a teaching method adapted to the learning style is more effective and increases retention or comprehension.

The reality

Unfortunately, no study has been able to prove that we learn better when training is adapted to our preference.

Evidence that this is a myth

- In 2015, Rogowski et al. hypothesized that “visual” people would learn better with written words and “auditory” people would learn better with an audiobook. Their study showed that both groups of learners learned better with the written text than with the audiobook.

- In 2017, Cuevas et al. also tested learning styles with university students. They found that learners who received the training material adapted to their preference did not retain information better than learners who received it in another style. On the other hand, they found that learners who received the information visually learned better than all learners who received it auditorily.

- In 2017, Paschler et al. conducted a review of the literature on learning styles. They concluded that “there is currently no adequate evidence to justify the use of learning styles in educational practice.”

The impact on our ways of doing things

Now that we all know it’s a myth, we must:

- Stop talking about learning styles to stop propagating the myth

- Vary the teaching methods and especially the ways of explaining

- Accompany verbal explanations with graphs or pictures

- Stop wasting time and money trying to adapt training to the learning styles of our participants

Myth #2

We only remember 5% of what we hear

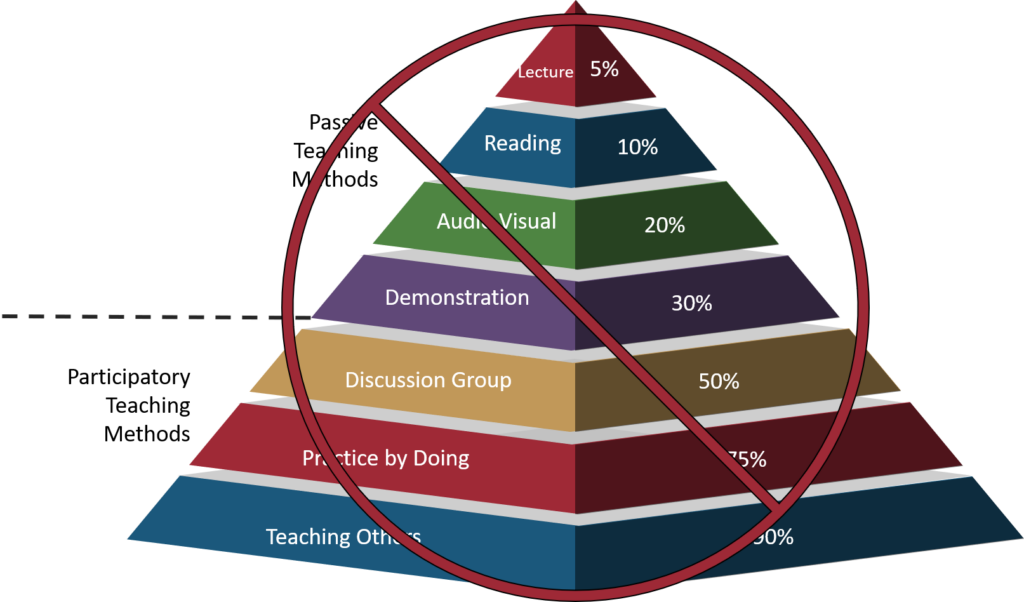

I often hear training professionals cite the “learning pyramid” to justify their pedagogical design. But where does this famous pyramid come from? And what is its validity?

The evolution of the myth

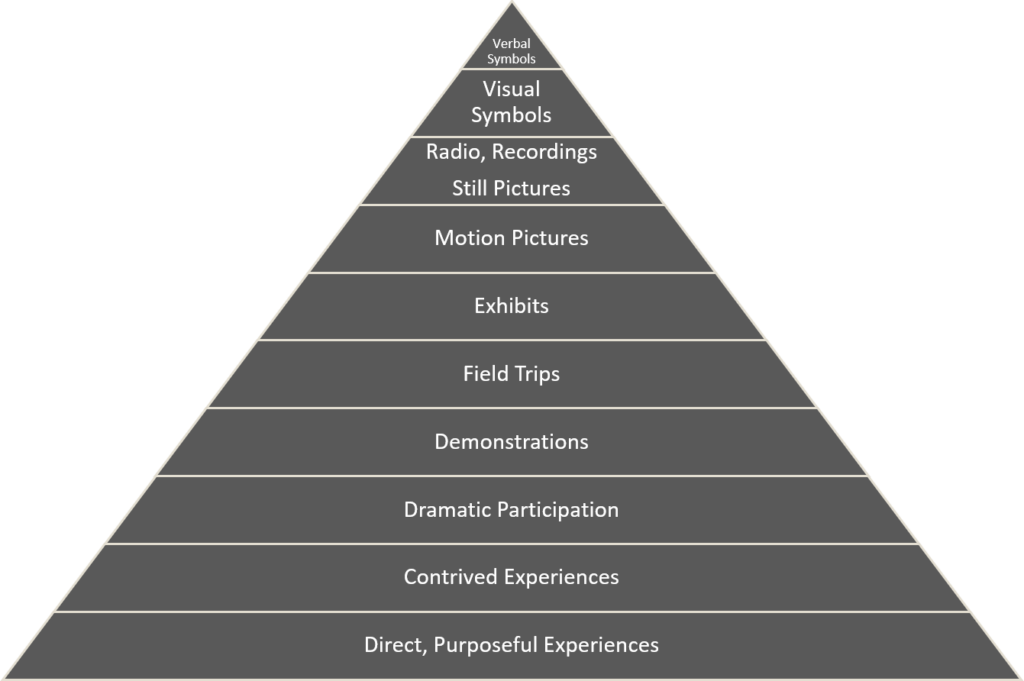

In 1946, Edgar Dale proposed a hierarchy of learning methods for adults. In this version, we can see teaching methods in a pyramid, without any numbers.

Over the years, people have misquoted Dale. In turn, these people have also been misquoted. One thing led to another as in the telephone game, and in 1960 Dale’s pyramid came to contain percentages — very accurate and all rounded to the nearest 5 or 10% — and the list, “People generally remember…”.

In 2002, Maine’s National Training Laboratories went even further and added the concepts of passive and active learning methods to the pyramid.

Several groups of researchers have studied the evolution of this myth and its explanation. Subramony et al. and Letrud, K., & Hernes, S. have written several articles on the subject from the perspective of the history of the myth in order to find out when the numbers appeared in Dale’s original scheme and was thus distorted. To my knowledge, no study has reproduced the figures in the pyramid.

Why the myth is stubborn

Because the theory seems valid and sensible, and because it supports what is instinctively believed about active and passive learning methods, it is widely adopted and repeated everywhere by teachers and trainers of all kinds.

The impact on the way we do things

Now that we all know it’s a myth, we must:

- Stop talking about the learning pyramid to stop spreading the myth.

- Select teaching methods based on our learning objectives, including lecturing, demonstrations and collaborative learning.

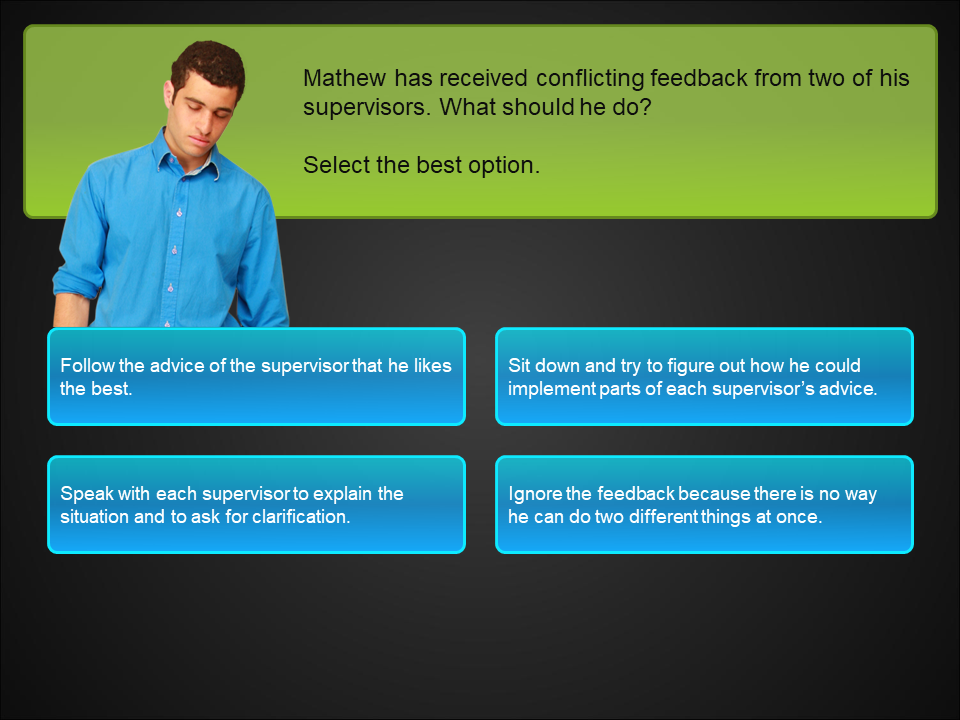

What do you think about this? Will you change your ways, knowing that these are myths?

Why is it so hard to get rid of your beliefs? Simply because we believe in our sources. In Blanchette Sarrasin’s study (accepted), teachers cite university, logic and practical observation as sources related to their adherence to myths. Where do your myths come from? From your colleagues, from your readings in popular science journals?

References

Blanchette Sarrasin, J., Riopel, M., & Masson, S. (accepté). Les neuromythes chez les enseignants québécois : à quel point sont-ils fréquents et quelle est leur origine? Éducation Canada.

Cuevas, J., & Dawson, B. L. (2018). A test of two alternative cognitive processing models: Learning styles and dual coding. Theory and Research in Education, 16(1), 40-64. doi.org/10.1177/1477878517731450

Letrud, K., & Hernes, S. (2016). The diffusion of the learning pyramid myths in academia: an exploratory study. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 48(3), 291-302.

Letrud, K., & Hernes, S. (2018). Excavating the origins of the learning pyramid myths. Cogent Education, 5(1), 1518638.

Masson, S. 19 et 26 novembre 2019. « Neuromythes ». Cours Neuroéducation et didactique générale. Montréal : Université de Montréal. Montréal : UQAM.

Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D., & Bjork, R. (2008). Learning styles: Concepts and evidence. Psychological science in the public interest, 9(3), 105-119.

Rogowsky, B. A., Calhoun, B. M., & Tallal, P. (2015). Matching learning style to instructional method: Effects on comprehension. Journal of educational psychology, 107(1), 64. doi :10.1037/a0037478

Subramony, D. P., Molenda, M., Betrus, A. K., & Thalheimer, W. (2014). Previous attempts to debunk the mythical retention chart and corrupted Dale’s Cone. Educational Technology, 17-21.

Subramony, D. P., Molenda, M., Betrus, A. K., & Thalheimer, W. (2014). The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: A Bibliographic Essay on the Corrupted Cone. Educational Technology, 22-31.

Subramony, D. P., Molenda, M., Betrus, A. K., & Thalheimer, W. (2014). Timeline of the Mythical Retention Chart and Corrupted Dale’s Cone. Educational Technology, 31-34.

Tokuhama-Espinosa, T. (2018). Neuromyths: Debunking false ideas about the brain. WW Norton & Company.