Using Active Approaches to Support Learning

By Sophie Lanoix

The lecture has had a hard life in recent years. As training specialists know, “active” learning methods are much more effective than “passive” methods. The lecture, seen as a passive learning activity, has therefore almost become a pariah amongst workplace training methods and to suggest using it sometimes amounts to blasphemy.

But why are active methods so much favoured? And are we really right? And to begin with, what is the difference between active and passive learning methodologies?

When Is a Learning Activity Active or Passive?

I often hear subject matter experts refer to an online course as “interactive” because it contains several videos and images that learners must click on to read additional information. As you have guessed it, this is not the right definition of “interactivity” in training.

In learning, when we say that a method is “active,” it means that the learner is focused on the learning content and that he or she must produce something with that content. Let’s illustrate this concept with an example.

Consider the case where a learner has to click on an element in an online course. This action can be “active” or “passive” depending on the context in which the learner must make the gesture of clicking on the element.

“Active” Learning Activity

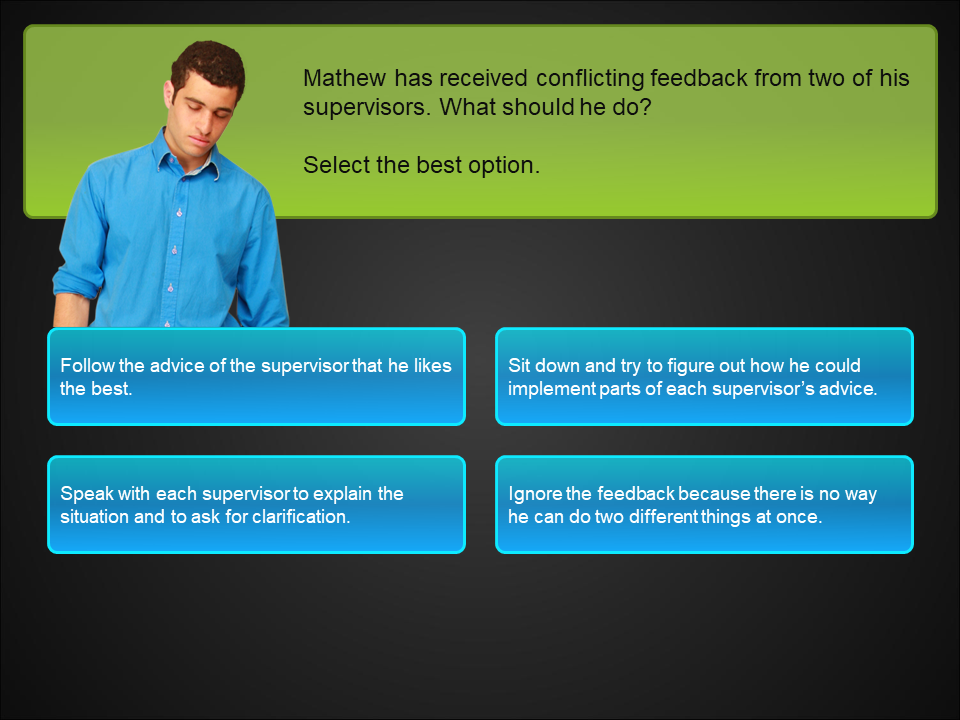

The learner clicks on one of four elements as an answer to a question.

This is an “active” action, because the learner must think about the question, analyze the four elements and consciously choose one of them as an answer. His brain is then engaged in learning, as he must use knowledge stored in his memory to answer the question. In this case, they must produce a response choice.

“Passive” Learning Activity

The learner clicks on an image to bring up the next text box to read.

Here, the learner does not have to select anything related to the content. Clicking on the image to bring up the next text box is equivalent to clicking on “next” to bring up the next page of the course. The learner has nothing to produce with the content.

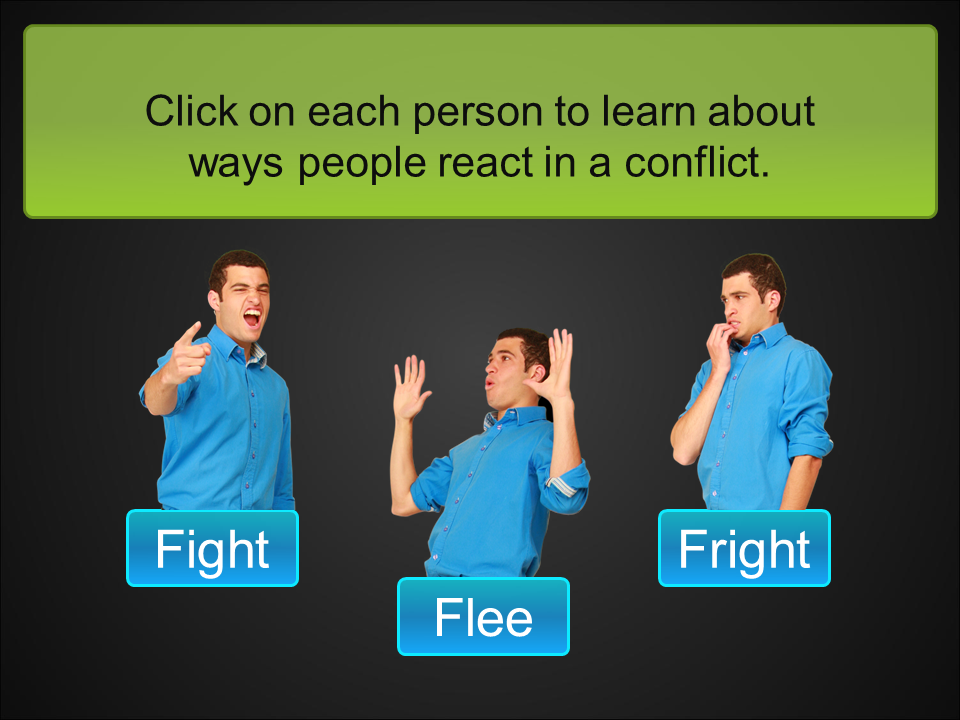

The same logic applies to classroom training. When the learner sits and listens to a lecture or watches a video, they are considered passive their learning. When answering questions, trying to solve a problem or analyze a situation, they are considered active in their learning, as they must activate their brain and use their knowledge to make connections between concepts.

Why Does the Brain Have to Be Active to Learn?

First, why do you offer training in your organization? Generally, because you want people to change their behaviour or adopt new ones. For example, if you provide leadership training, it is to make managers change the way they manage and be more effective and efficient. If you provide training on the use of a forklift truck, it is because you want employees to adopt safe behaviours when using the forklift.

To answer the question, “Why does the brain have to be active to learn? ,” you have to look at what’s happening in the brain while a person is learning. A person’s behaviour depends on their neural connections. To change behaviour, we must therefore create new neural or even create new neurons. This is the very definition of learning in neuroscience.

When a person learns a new skill or behaviour, neurons are activated and they connect together. If these neurons activate and connect together often enough, a path is created between the neurons, like a path in the forest. When the path is well traced, the skill or behaviour is well anchored, and the person is able to reproduce it. The more the trail is used, the deeper it is traced, the easier it is to follow. So, the more often you perform a gesture, the better and easier it is to remember.

Hebb’s Rule: Cells that fire together, wire together

Some examples of active learning activities

In an asynchronous online course

- Associating an image with a word or concept

- Answering a multiple-choice question, whether the options are presented with words or images

- Putting process steps in order

- Dragging and dropping a word or image into the right area

- Identifying errors or good elements in an image

- Etc.

In a physical or virtual classroom

- Explaining a concept to a colleague

- Answering questions

- Writing a case study

- Explaining the consequences of an action

- Analyzing the possible options for solving a scenario

- Making the gestures of the psychomotor skill to be acquired (driving the forklift, using medical imaging equipment, handling an instrument, etc.)

- Practising a communication skill in a role-playing game

- Etc.

So, Should You Throw Away Passive Methods?

That being said, we also learn when we read a text or listen to a masterful presentation, even if we consider them passive learning activities. Studies have shown that when an action is observed, the same neurons are activated in the brain as when the action is performed. So, if a learner is attentive and able to mentally follow the actions that the trainer explains during the lecture, learning begins in their brain. However, behaviour or knowledge will not be well anchored and active learning methods will be needed to consolidate them.

Passive methods such as lectures, video playback or reading are still useful. They are preferred when the task is completely new to the learner, or when the risk of error is very high. They will be used to lay the foundation knowledge that learners can then use to practise the skill with more active learning methods. In addition, lectures allow trainers to explain nuances more effectively than a text, to model behaviours and values and to stimulate learners’ motivation.

Conclusion

I admit it: I am one of those people who make life difficult for lectures and passive learning methods. However, I also recognize their value in certain circumstances. I still remain a strong supporter of active methods, especially considering that learners who enter our workplace training generally have prior knowledge related to the subject of the training. It is much easier to acquire new knowledge and skills when you are able to connect them to things you already know.

We have created a simple and easy to use

Learning Method Variety Grid

to help designers determine how passive or active their online, classroom or virtual courses are.

Do you have any questions, comments or reactions? Feel free to share them with us in the forum below. Are you hesitating? You can write to us in private.

Need a helping hand to dynamize your training?

We can help you.

Contact us!

Spread the word!

Facebook-f

Twitter

Linkedin-in

Instagram

Envelope

References

Bradbury, N. (2016). Attention span during lectures: 8 seconds, 10 minutes, or more?. Advances In Physiology Education, 40(4), 509-513. doi: 10.1152/advan.00109.2016

Lachaux, J. (2013). Le cerveau attentif. Paris: O. Jacob.

Masson, S. 10 septembre 2019. « Principe 1 : Activation ». Cours Neuroéducation et didactique générale. Montréal : Université de Montréal. Montréal : UQAM.

Masson, S. 17 septembre 2019. « Principe 2 : Activation répétée ». Cours Neuroéducation et didactique générale. Montréal : Université de Montréal. Montréal : UQAM.

Masson, S. (2016). Pour que s’activent les neurones. Les Cahiers pédagogiques, 527, 18-19.

Mukamel, R., Ekstrom, A., Kaplan, J., Iacoboni, M., & Fried, I. (2010). Single-Neuron Responses in Humans during Execution and Observation of Actions. Current Biology, 20(8), 750-756. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.02.045

Tokuhama-Espinosa, T. (2018). Neuromyths (pp. 147-149). New York: W.W. Norton & Company.